For November’s object of the month, we have decided to bring to light not just one artifact from our collection, but a whole group. On our social media, we have been posting about some of our extinct species specimens for Remembrance Day for Lost Species day on the 30th of November. Here we have compiled all of their stories into one place allowing for additional information to be added so that you can get a much more in-depth understanding of what happened to these incredible creatures. All these specimens are open for viewing in our World Wildlife Gallery.

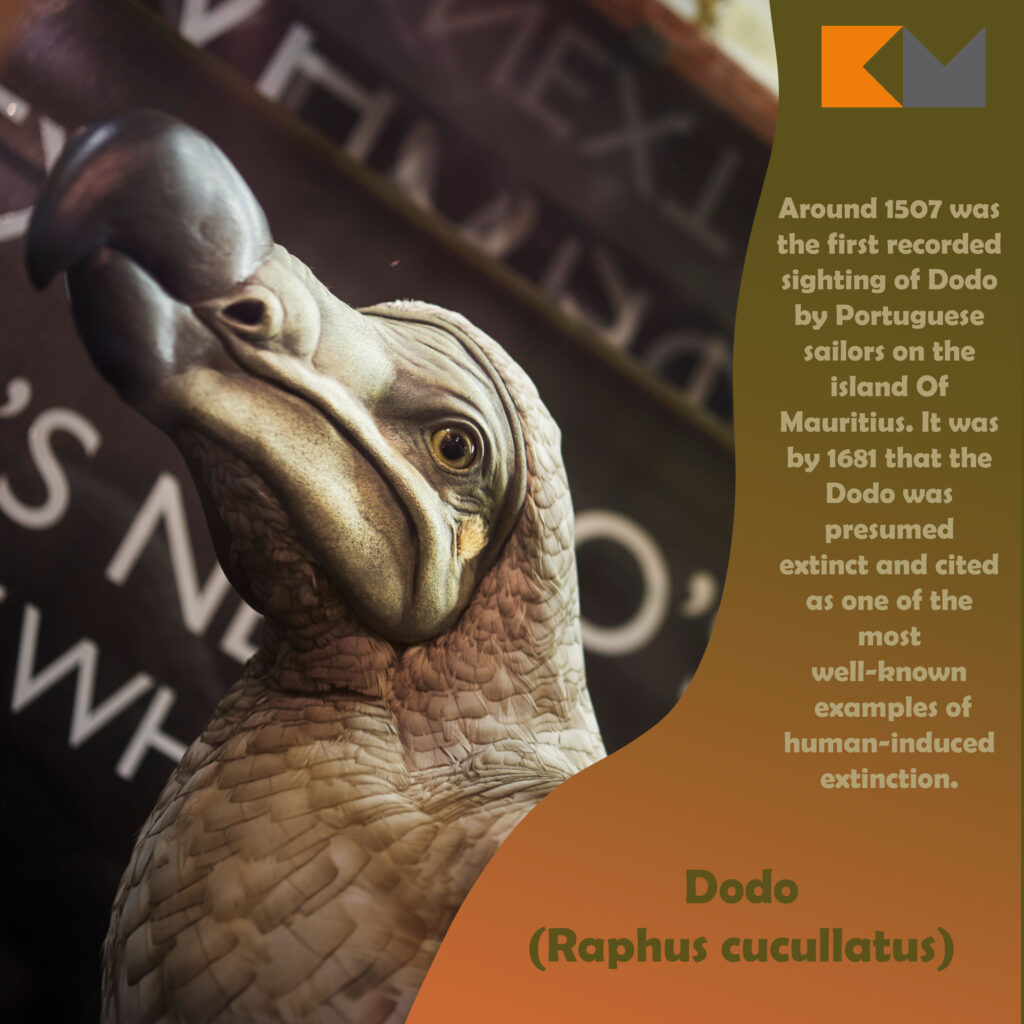

Dodo

To start our lost species mini-series I thought we’d kick off with probably the most famous extinct creature to date, the Dodo. Unfortunately, the Dodo became extinct nearly 100 years after it was discovered. It was around 1507 when they were first discovered. Sources state that it was either Portuguese or Dutch sailors that first recorded them. The three main contributors to why the Dodo became extinct were hunting, deforestation, and the introduction of non-native species. They were famously flightless birds with no natural predators on their home Island of Mauritius, so undeterred by the sailors when they arrived. This led to them being extremely easy to hunt. Another problem was the non-native species that were introduced at the time. Arrivals of dogs, cats, rats, and pigs caused immense damage to habitat, nests, and eggs, and a general depletion of food for the Dodo itself. All this led to the last confirmed sighting of the Dodo in 1662.

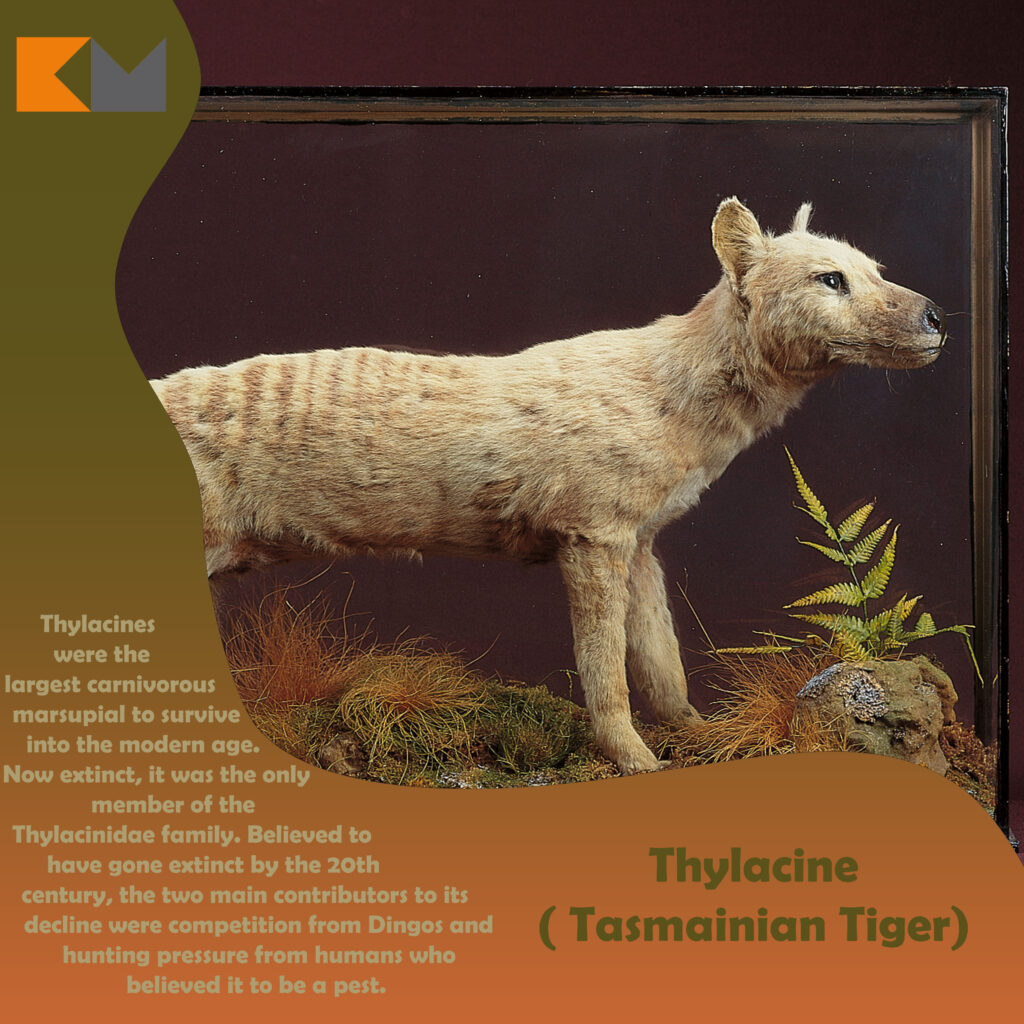

Tasmanian Tiger

Next in our mini-series is the Tasmanian Tiger, better known as the Thylacine. A native species to mainland Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania. Its depletion is all thanks to the same few common factors, hunting, habitat destruction, and introduced disease. Australian sources claim the main reason for Thylacine demise was growing competition from the Dingo. However, Tasmania and New Guinea collectively blame the hands of European settlers.

It was estimated that around 5,000 Thylacines were in Tasmania at the time European settlers arrived, but alongside new people came new animals. With domesticated sheep arriving and the Thylacine being labeled as a threat to livestock, this marked the beginning of the end. As early as the 1830s a bounty system was established and put in place. This program lasted until 1909 and awarded 2,180 bounties; it is estimated that about 3,500 Thylacines had been killed between the 1830s and the 1920s. To add insult to injury for the Thylacine, diseases such as mange were introduced and then habitat destruction was also added to the list of problems this species had to face. By 1914, it was considered rare, and by 1936, the last known living specimen died in a private zoo. Its disappearances from the wild followed two years later. Though considered extinct, sightings of the Thylacine continued to be reported throughout mainland Australia and Tasmania since the late 1930s.

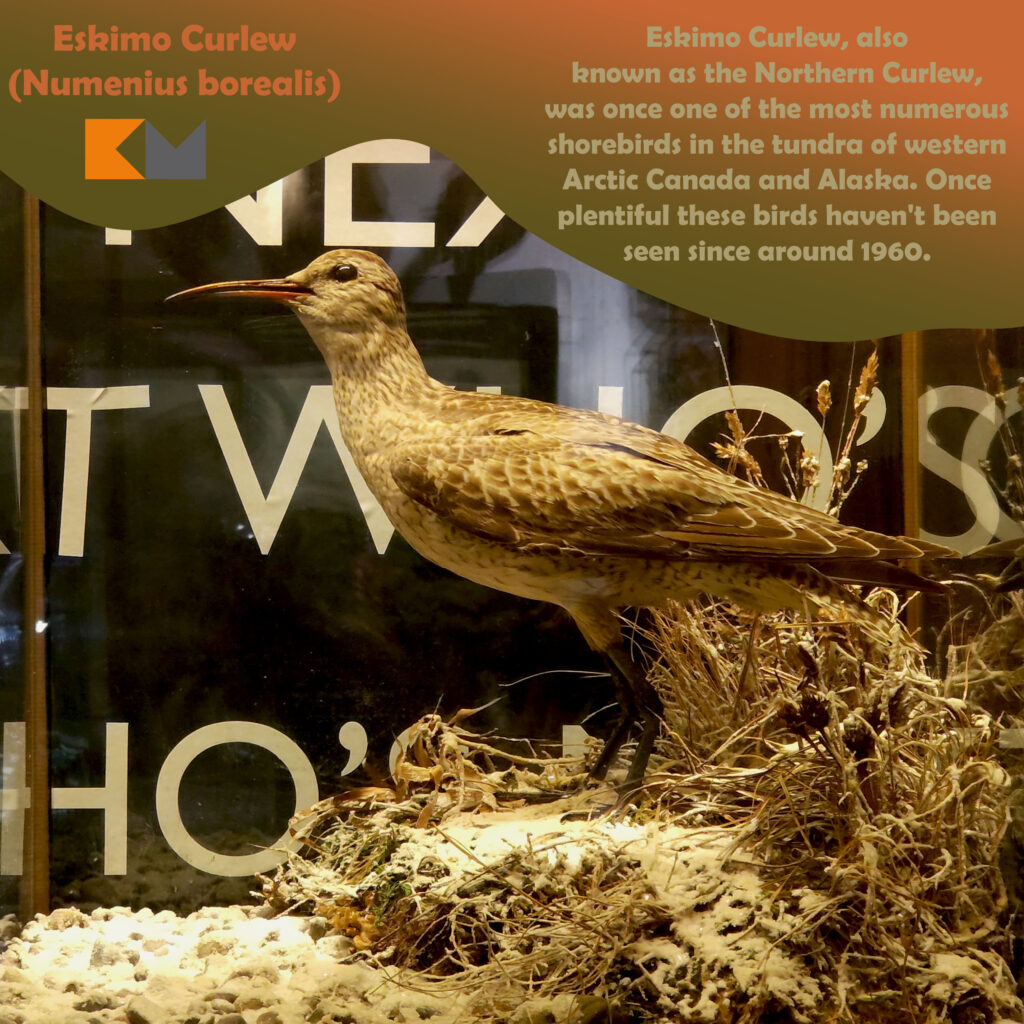

Eskimo Curlew

The third in our series is the Eskimo Curlew. At one point, this bird would have been one of the most numerous shorebirds in North America, with numbers in the hundreds of millions. Due to ‘market hunting’ – an unfettered and often profligate practice of killing wild birds for consumption that flourished in the 19th century. It was often referred to by hunters as “doughbird” because of its ample fat reserves. This, combined with habitat loss, with migratory stopovers turned into agricultural fields. Settlers also began to suppress the wildfires that burned across the Great Plains. This removed the large-scale habitat disturbances that favored curlews and their feeding habits. Alongside all of this, the primary food sources of the Eskimo Curlew, the eggs and larva of the Rocky Mountain locus are going extinct. In 1966, the Eskimo Curlew was among the first species listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, the predecessor to today’s Endangered Species Act.

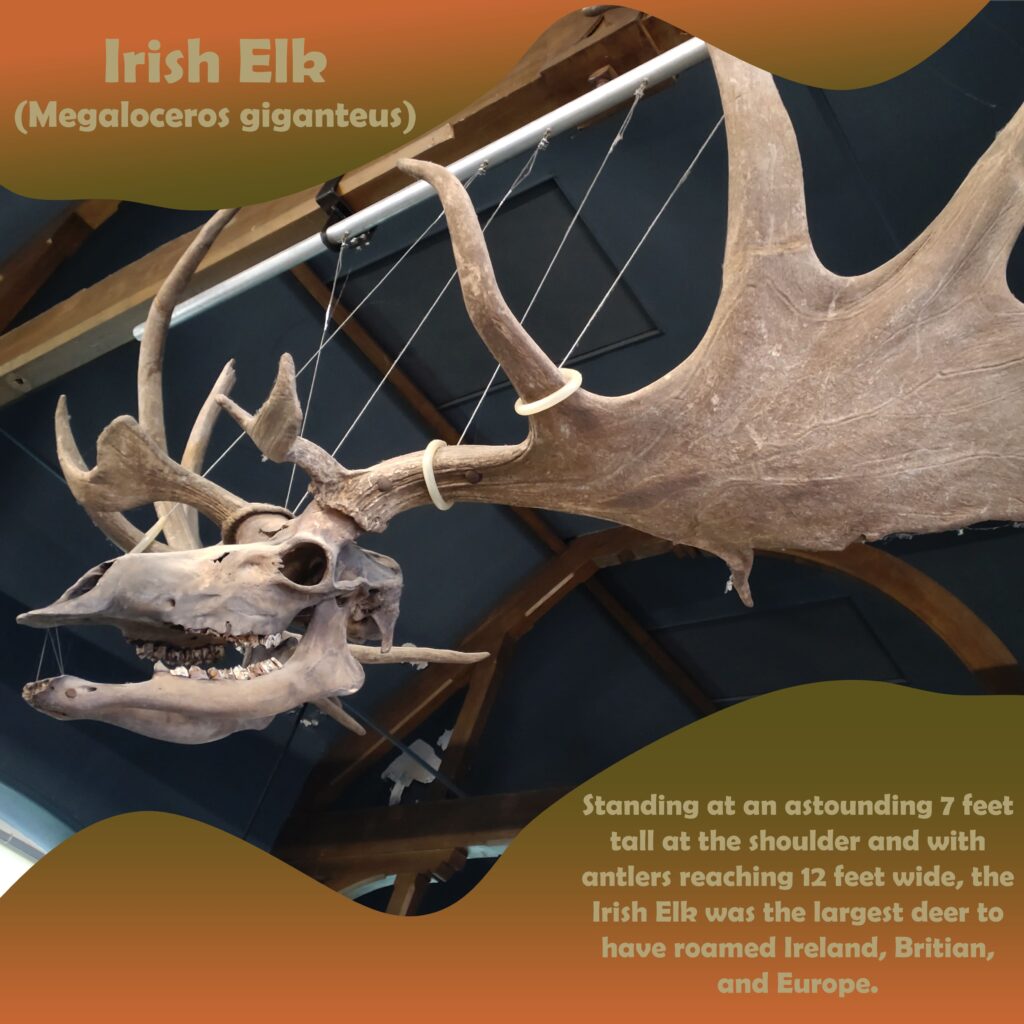

Irish Elk

In the instances of the Irish Elk, however, early humans didn’t play a big role in its downfall, with very little evidence showing that early man ever hunted Irish Elk. We, however, were competing for the same habitat spaces that were rapidly declining. The name Irish Elk is rather deceiving given that its domain reached across all of Europe, including Ireland and Britain. It’s not even part of the Elk family, with its closest living relative being the Red Deer native to the British Isles. The reason for its extinction comes down to the fact that around 12,000 years ago the earth’s environment and climate were rapidly changing thanks to the coming end of the Ice Age. This was when the first wave of extinction occurred, with increasingly freezing temperatures wiping them out from Britain and Ireland. Then, around 8,000 years ago, the last remaining population of Irish Elk from what is now Russia began to die out. Now rising temperatures that encouraged forests and woodland to pop up and expand across their preferred grassland habitat.

New Zealand Huia

Finally, our last installment is the New Zealand Huia, a rather tragic downfall came to this once sacred bird. During pre-European times Huia ranged over the whole North Island by the 19th century, they were confined to the wilder mountain areas on the southern half of the North Island. Sadly, like many New Zealand birds, the Huia became victim to the twin pressures of hunting and habitat loss.

Even though its mature rainforest habitat didn’t face much loss its lowland refuge from the colder months was decimated.

Hunting, however, was driven forward because of two main factors. The first had to do with Pākehā men (white New Zealanders) who soon copied the Māori custom of wearing Huia feathers in their hatbands, Huia plumes had been reduced from a sacred treasure to a mere fashion accessories. The second reason is particularly tragic; the naturalists of the day had identified the Huia as an avian wonder, leading the harvesting of specimens for museums and private collections to boom.

Nowadays we are much more aware of human impact on animal populations. At Kendal Museum we are starting a project to include more information about these tragic histories, see our Reimagining project page to get involved.